Jack Hill: Exploitation Cinema Auteur

From The Grindhouse Cinema Database

Writer/director Jack Hill's name will forever be associated with films that feature strong, ethnically diverse and sexually liberated women in leading roles. Though his directorial debut came in 1964 with the campy horror classic Spider Baby (released in 1968) Hill made his mark with two women-in-prison films; 1971's The Big Doll House which he also produced, and 1972's The Big Bird Cage which he wrote and directed. Both films were audience favorites: packing them in at downtown theaters as well as in Drive-Ins. 1975's Switchblade Sisters—which he wrote and directed, remains a cult classic cited by many as the quintessential female gang film.

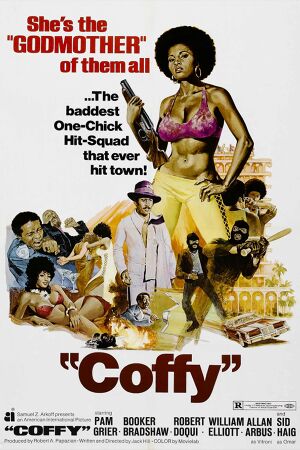

Even so, it was Hill's foray into blaxploitation that cemented his status as an industry craftsman who possessed the skills, knowhow and desire to give audiences exactly what they came to see. 1973's Coffy was a runaway hit. One of only four blaxploitation films (out of more than two hundred) to top Variety's all-important Top Grossing Films list. It also ignited a black “female-hero” sub genre—Emma Mae, Sugar Hill, TNT Jackson, Velvet Smooth—and made Pam Grier a star.

1974's Foxy Brown was Hill's follow-up to Coffy. Written and directed by Hill, Foxy Brown's effect on popular culture was immense. Rapper Foxy Brown later took her name from the titular film character while Quentin Tarantino payed homage to it with his update Jackie Brown.

It's been more than forty years since Jack Hill's films reigned supreme. 1982's Sorceress was a disappointment so profound that Hill, who directed and co-wrote the screenplay, had his name removed from the film. It also facilitated a lengthty sabbatical from the movie industry.

The following interview first appeared in my book Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide. Since that time Hill has become a coveted guest speaker on the exploitation and blaxploitation film genres. He also continues to write, has several projects in the works and is excited about his “very ambitious” novel.

“The Big Bird Cage” was your first film to feature a strong black subplot. How did you come to write and direct it?

I wouldn’t say that it had a “black subplot” by any understanding of the term that I have. Two of the characters just happen to be black. So what? But I must admit that Pam Grier, the main black character in the film, makes quite an impression and she has the best line. After a white gall calls her “nigger,” Pam floors her and says: “That’s Miss Nigger to you!” Pam came up with that line; I would never have thought of such a thing.

You first directed “The Big Doll House” but someone else wrote the script. Was it easier for you to do the follow-up “The Big Bird Cage” given the fact that you both directed and wrote the script?

The Big Bird Cage was much simpler to shoot, mostly because I didn’t have to rewrite almost every scene and even invent new ones, as I had done on The Big Doll House. Hmmm…now that I think of it, maybe I should have.

What were your ideas about the blaxploitation films when you made “Coffy”?

Well, I had seen and admired Super Fly, but as a white man I didn’t feel truly qualified to handle black characters and lifestyle on that level of reality. I also felt that black writers and directors should have the first crack at the opportunities that the success of the genre presented.

What changed your mind?

Larry Gordon. He was then head of production at American International Pictures. He called me in and asked if I could create a “black woman’s revenge” picture. I said I thought I might be able to do it if I could work with Pam Grier. I had helped launch Pam’s career a few years earlier and thought that she was the only actress that could generate the kind of screen persona I had in mind. To me, Pam has something magical; I can’t put a name on it. Just “It”! That special thing that only she has. (Ed. Note: Coffy was commissioned so that it would directly compete with Warner Bros’ simultaneously released Cleopatra Jones.)

“Coffy,” even by today’s standards, remains shocking. Did the violent situations, nudity and profanity present any special challenges?

By this time in the history of cinema, we were all used to it. I don’t recall any profanity, though. I mean, nobody used “fuck” as an expletive, did they? (Ed. Note: They do, many times). The only challenge I recall was the fact that when we made the picture there were no experienced black stunt coordinators—and even more sticky for an action picute like Coffy, virtually no black stunt women. Which meant we had to train people on the job, presenting a serious safety concern that casued many a pair of crossed fingers on the set at times.

The film seems specifically created to shock and titillate.

You mean “shock and awe”? What the hell—why not? But titillate! Perish the thought! Well, I can only say that I had to fight the studio to make the film something more than shocks and titillations. The “awe” was my contribution.

How long was the shoot? What was the budget like?

Eighteen days; $500,000.

“Foxy Brown” came fast on the heels of “Coffy”. Did you have a freer hand given your success with “Coffy”?

Nobody had any idea that Coffy would be such a big hit, so nobody gave any thought to a sequel—least of all me. Did I have a freer hand after that? On the contrary! The studio idiots were afraid after such a big success I might have a big ego, so they tried to put me on an even tighter leash. But I fooled them.

Did you feel you were under pressure to do a bigger, more outlandish follow up to “Coffy”?

Only because I hated the studio system so much at that time that I felt that only by really going over the top could I get my own sinister kind of revenge. Unfortunately, the result has haunted me ever since.

It’s certainly a more colorful production.

If you mean the title sequence and all the costume changes, which I didn’t like at the time because I thought they took attention away from Pam’s performance and beauty, I guess your right. People think the budget for Foxy Brown was bigger than Coffy, but it actually ended up being less. $500,000 was all AIP was willing to pay for one of their so-called “black” pictures, and because they had to pay me and Pam more the second time around, there was less money for the actual production. Even so, I brought it in a day early and became of that, became a hero at the studio.

It doesn’t sound like “Foxy Brown” is a favorite film of yours.

Well, as you know, originally, I wrote the script as a sequel called Burn, Coffy, Burn. We were all pretty upset when, at the last minute, the studio decided to change it. One of the geniuses in the marketing department told the studio that sequels weren’t making any money. (Ed. Note: It was, in part true: AIP’s Scream Blacula Scream—a follow up to the super successful Blacula, was a surprise flop.)

What is your opinion of “Foxy Brown” today—I mean, it’s been appropriated everywhere.

I like it and I understand why it’s preffered to Coffy. But, even so, I believe Coffy is the better film. My feelings about Foxy Brown are mixed but, still, I would rather have made Foxy Brown than The Godfather III!

“Switchblade Sisters” followed “Foxy Brown” and is in many ways a “whitesploitation” film.

Well, somewhat, yes. I really tried to do something special with Switchblade Sisters: a female version of the basic triangle of Othello—dealing with a woman provoking another woman’s jealousy. When I first saw it in a theater with an audience I felt that I had done everything wrong that I could possibly do wrong. Now it’s considered a classic—post modern—etc. Just goes to show you how things are reevaluated with time!

Many blaxploitation-era producers and directors have spoken about racism behind-the-scenes. Did you witness any of this?

Plenty. I was frankly appalled at some of the things I saw and heard. The studio had nothing but contempt for the audience they were making films for, but not just the black audience—everyone. They weren’t shooting for an Academy Award, those guys—they had a popcorn machine in the screening room. But the studio executives weren’t the only racists: film critics were too. I remember one reviewer referring to the character of Coffy as “an unsympathetic black chick”; another as “a black tart.”

But your experience making the pictures was a positive one?

Yes. It was one of my most enjoyable experiences to collaborate with those wonderful young black players—so much enthusiasm, so full of marvelous ideas to enrich their characterizations and contribute elements to the film that, alone, I could never have dreamed of. They also were thrilled to finally be actually working at last. It was the age of “black power” and “black is beautiful”—and it was beautiful, and it was powerful. It still is!

How would you like to be remembered?

One of my greatest satisfactions is that films like Coffy, Foxy Brown and a few others demonstrated that black stories, characters and lifestyles could appeal to both black and white audiences: they called it “cross-over audiences” at the time. Ultimately, I think my work helped open doors for black men and women in all categories of the film industry. So, if I contributed in any small way to a new consideration of blacks in films, I will be forever grateful.

Jack Hill Films on Blu Ray

Josiah Howard is the author of four books including Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide (now in a fourth printing). His writing credits include articles for the American Library of Congress, The New York Times and Readers Digest. A veteran of more than one hundred radio broadcasts, Howard also lectures on cinema and is a frequent guest on entertainment news television. Visit his Official Website.