Arthur Marks: Exploitation Maverick

From The Grindhouse Cinema Database

Writer/producer/director Arthur Marks is known by those in the film industry as the man who created and headed GFC, General Film Corporation, an independent distribution company that also produced low budget films for the Drive-in and inner-city film markets. Film fans know him for another reason: his prolific work—five dynamic blaxploitation films (he’s one of only three producer/directors with five or more genre films to his credit.)

Arthur Marks began his show business career in television directing shows like “Perry Mason” (76 episodes), “I Spy,” and later “Starsky & Hutch” and “The Dukes of Hazzard.” His first theatrical release was 1970’s Togetherness. That was followed by Gabriella (1972), Bonnie's Kids and The Roommates (both 1973).

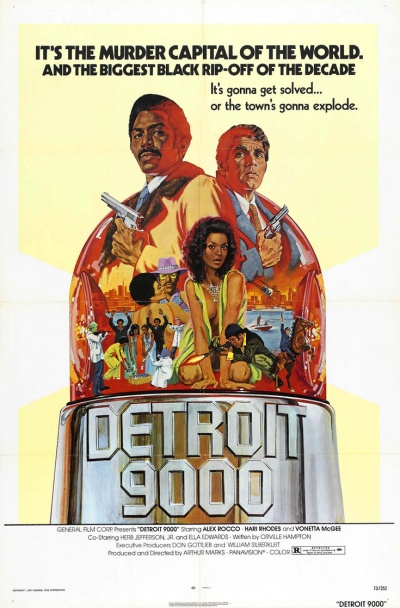

1973 was also the year that he made an indelible mark on the entertainment industry. Detroit 9000 (which he produced, directed and distributed through his own company GFC) set a new bar for blaxploitation films. Best known a showcase for action sequences, car chases and narratives focused on illicit activities, Marks contribution to the popular genre (more than 200 black-cast films in ten years) included dynamic locations, on-the-rise character actors, and a host of distinctly positive role models. “At the time no one looked to blaxploitation films for great acting performances or uplifting storylines,” remembered Marks. “So that was one of the things I wanted to contribute. A few of my films showcased stars but most featured talented actors that I wanted to give a break.”

And there were plenty of films in which they might be cast. Bucktown hit theaters in the summer of 1975 and starred two of the genre’s most popular performers: Pam (Coffy) Grier and Fred (Black Caesar) Williamson. Just a few months later Marks’ Friday Foster a live-action adaption of a comic strip, further cemented Pam Grier as a black feminist icon. 1976’s J.D.'s Revenge was a mystery/horror thriller with a largely unknown cast and The Monkey Hu$tle (sic) was a black-cast homage to the white-cast hit The Sting. Marks directed and produced both films.

When I interviewed Arthur Marks for my book Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide I found him prepared and engaging: “I’ve put aside an hour,” he informed. We spoke for two. Although Marks was clearly a craftsman and an artist, he also had an invaluable understanding of the business side of filmmaking, in particular trends, profit margins and studio expectations. He is one of very few directors from the time who formed his own distribution company, shepherded it to success, and then, seeing the writing on the wall, sold it: at profit. “Nothing lasts forever,” he told me and that was certainly true with blaxploitation films—whose top moneymaking days were 1971-1974. “When the business you’re in changes, it’s time for you to make a change too.”

Arthur Marks’ decades-long experience has made him a coveted speaker on college campuses and at cinema conventions. On August 2, 2018 he’ll celebrate his 91st birthday.

Josiah Howard Interviews Arthur Marks

Detroit 9000 was your first venture into blaxploitation. How did it come about?

Well, at the time I was heading General Film Corporation. I saw a Time magazine cover story whose focus was the fact that Detroit, Michigan was the murder capital of the world. I thought 'There’s a movie in there somewhere.' I presented the idea to a few important people and took it from there. (Editors Note: “Detroit 9000” is police code for “officer needs assistance.”)

Did you set out to write a blaxploitation film?

No. originally the film was designed to be a white picture starring Alex Rocco. He had just done The Godfather and everyone was predicting he would be the next big thing. But the Drive-in market had no interest in him: they wanted a “black” picture that could play “downtown” and at the Drive-ins. That was the market we were making the film for so that’s what I gave them.

The rapid-fire editing is forward thinking: it looks totally contemporary.

I think so too. I remember I was in a meeting with Sam Arkoff who was the head of AIP (American International Pictures). Sam was very concerned about Detroit’s quick cuts and fast pace. At the time the movie companies thought that black audiences didn’t want to be barraged with images. They thought blacks preferred viewing films with steadily progressing narratives; scenes that they could view, digest, and move forward from in a linear fashion. At one point they were going to completely re-edit the film. I told them they were crazy and that I didn’t know how they did their research but they were wrong. My opinion was that black audiences would experience the film exactly the way white audiences would—and the rapid-fire editing would appeal to both.

Does it surprise you that the picture has such a large cult following?

Yes, it does. I thought that it was always a good professional film, but I never expected it to remain so popular: especially thirty years after the fact. About two years ago I got a call from Quentin Tarantino. He told me he was a huge fan of the film and thought it should be re-released. We had a meeting and that lead to the updated Rolling Thunder Pictures DVD release and a limited theatrical run. Tarantino’s endorsement brought it to a new generation. What was a pleasant surprise to me was that the new generation had a real interest in seeing it.

You seem to make location—Detroit, Washington D.C., New Orleans, Chicago—a major part of your storytelling.

That is a very astute observation. Yes, I did that on purpose. I felt that genuine locations would not only enhance the story and add to the realism of the pictures but would also increase the likelihood that the films would be played in the cities we were featuring. And there was another reason I chose to work on location: it allowed me the opportunity to do things that I wouldn’t have been able to do in a union-based Hollywood. There was more freedom when you were off the backlot. To be sure, the studios still sent out executives to check on the shooting and make sure we weren’t going over budget, but they were only in town for a short period of time. They wanted to get back to their comfortable desks in Hollywood.

Your films also share a readily identifiable format; they start out with a bang, either literally or figuratively, and then move forward from there.

The blaxploitation films I did were created to grab hold of an audience in the first ten to fifteen minutes and keep them hooked for the duration of the picture. If you’re not hooked in the first few scenes of an “action” film you might not get hooked at all. Remember, the films were made for a young teenage audience. Be it at the Drive-ins or downtown, the movies had to have punch. I didn’t want the audience to wait.

Bucktown and Friday Foster were both released in 1975. Which was finished first?

I think we did Bucktown first. we were on a schedule to get the pictures out fast. Even then, the studios were aware that the black action genre was going to have a limited run. Everything had an expiration date. Looking back, I really don’t know how I did it: five films in three years is pretty outrageous!

Was it difficult working with a star like Pam Grier, someone who had a very powerful preexisting image?

At the time I cast Pam in Bucktown she was doing these shoot-‘em-up films filled with big breasts and scanty clothes. I met with her, talked to her, and told her that if she would lend herself to me, I would feature her in a film that she could be proud of. I told her ‘You’re going to play a waitress, a gal who works in a bar, who falls in love with a guy from Philadelphia and it’s going to be a love story. You won’t be shooting anyone or any of that stuff; your job is to provide a solid base as to why he wants to stay in this small town.’ She loved the idea: that I was considering her seriously and I think she did an excellent job.

Then I cast her again in Friday Foster and we got her everything she wanted; good clothes, expert makeup, perfect hairstyles—the whole glamour treatment. She had a ball. Pam really felt like a star in Friday because it was more like a mainstream picture than a blaxploitation film. It proved that she was capable of carrying a film on the strength of her acting.

In J.D.'s Revenge your use of B/W and color photography is very interesting. Was this difficult to accomplish?

In those days we didn’t have sophisticated computers or visual effects, so we just shot a lot of the scenes in B/W or sepia right on the spot: there was no post production, everything was improvised. I think the end result was good: it was something different in a blaxploitation film; something interesting. The audience didn’t expect it and it wasn’t in any of the press so they were surprised.

Was the film inspired by The Exorcist or the Reincarnation of Peter Proud—both popular occult-themed films at the time?

No, not really. I liked the J.D. script and thought it would be a perfect vehicle for Glynn Turman. I had seen Glynn in Cooley High and thought 'Now there’s a really fine actor.' It’s true that there were a lot of horror films out at the time and that they were particularly popular in the exploitation/blaxploitation markets. But I think J.D. was different. It may have looked like all the rest but it wasn’t.

The Monkey Hu$tle is a “feel-good” film, very different than “J.D.'s Revenge”. Did you make a conscious effort to depart from the action-adventure genre?

Oh, yes! As a matter of fact, I wanted to do Oliver. That’s what Monkey Hu$tle is; Oliver in Chicago with a black cast! Yaphet Kotto is Fagan, and the boys are all his gang. It’s a great film and audiences really loved it. the interactions that the characters have with each other is just superb. That was one for the families.

Listen to the score from Detroit 9000 by Luchi DeJesus

How did you come to cast raunchy comedian Rudy Ray Moore?

I had never seen Rudy in any of his films but someone told me that I should really see Dolemite; that he would be perfect for the part of the flashy, loud-talking character Goldie. I arranged a meeting to hear him read and he did: but he was dreadful. I thought ‘this is the person everyone wanted me to audition?’ So, then I threw away the script and told him to just be himself. When he was reading the script, he was trying to guess what I wanted him to be, when all I wanted him to be was himself. We sat and talked for a while and soon Rudy felt comfortable and started telling his funny stories. In the end he was terrific: exactly what the film needed. I hired him on the spot. (Ed. Note: A film about the making of Dolemite is being re-made this year starring Eddie Murphy as Rudy Ray).

What was your opinion of blaxploitation pictures at the time?

I must say that I often thought that blacks were presented very, very poorly. I won’t mention any director’s names, but more than once I voiced my opinion. I said: ‘You know, you’re really off base here. You really are making a ‘Black Exploitation’ film.’ I was concerned because the negative portrayal of blacks and black life in some of the pictures was giving directors like myself a bad name.

Did you ever experience any racism in Hollywood?

No, I never felt it anywhere. But don’t forget that I was an independent and pretty much did what I wanted to do: that’s why I was an independent! Also, me being away from the studio on location shoots so much meant that I had created a healthy distance. I wasn’t really involved with the studios or their politics.

Why do you feel the genre came to an end?

I really can’t answer that one: it’s still not clear to me. I’ll tell you why the Drive-in market dried up. The big studios took a look at the money that independent films were making in the exploitation and black markets and made their own exploitation and black films. Because the big studios could spend a lot more money on advertising, they pretty much pushed the independents out business. The majors placed their movie ads on television. We, the independents, placed ours on radio and in newspapers. There was just no way we could compete.

I had a conversation with Sam Arkoff at AIP and he told me that the only reason he sold his company was because he couldn’t make a profit anymore. All across the country Drive-ins were disappearing and Hollywood didn’t want to supply their films to that market. When they did, the prints were old and scratched and the film had already played out in theaters. They gave us the leftovers. Hollywood made a concerted effort to put the Drive-in and independent exploitation movie market out of business. They wanted that money too.

Why do you believe blaxploitation films remain popular today?

Plain and simple: they’re worth seeing again.

Arthur Marks on BluRay

Josiah Howard is the author of four books including Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide (now in a fourth printing). His writing credits include articles for the American Library of Congress, The New York Times and Readers Digest. A veteran of more than one hundred radio broadcasts, Howard also lectures on cinema and is a frequent guest on entertainment news television. Visit his Official Website.